Why Do We Define Risk So Narrowly?

The situation was messy and risky. A supervisor was fired for bullying members of his team. The VP overseeing the dismissal wanted to disclose his reasons for select audiences, including some staff and local churches. But, fearing a defamation lawsuit, our in-house lawyer was dead set against doing so.

If risk management is defined as limiting legal exposure and protecting ministry funds, then the lawyer was 100% correct. It would have been foolish to ignore his advice.

But, as the VP retorted, there were other risks involved. How might organizational silence impact staff morale (those who had been mistreated)? Public perception (covering up for a bad actor)? Ongoing ministry culture (creating distrust)?

During the next several months, my senior leadership team engaged in lengthy conversations about defining risk. Since it lurked everywhere – e.g., deploying volunteers, running camps, and sending students on mission trips – this was a critical discussion.

A More Robust Definition

Eventually, we expanded our definition of risk to include five factors. These included both “hard” (measurable) and “soft” (difficult to measure) considerations:

- Mission Risk – Would we be diverted from accomplishing our core purpose?

- Morale Risk – Would staff esprit de corps be undercut?

- Legal Risk – Would we expose the ministry to lawsuits or governmental action?

- Fiscal Risk – Would the ministry’s financial health be imperiled?

- Reputational Risk – Would long-term trust be undermined with donors and the general public?

In the dismissed supervisor situation above, how might these factors interact?

If multiple staff decided to quit, campus ministry would be set back for years (mission risk). Even if they stayed, trust would suffer if the national office handled the matter with a full non-disclosure agreement (morale risk). In addition, the former supervisor might do harm elsewhere if we failed to warn other ministries about him (reputational risk).

Since a robust insurance policy mitigated our legal and fiscal risks, I allowed limited disclosure to select audiences. The affected staff remained, and the ministry moved forward.

Other Steps

A byproduct of redefining risk was moving this management function from a specialist to a senior team. While this may seem counter-intuitive – why add more work to our plates? – it reduced stress, resulted in better decisions, and fostered a greater sense of agency. VPs felt like they had more input into important decisions.

We also instituted a multi-step “decision tree.” Whenever our CFO, HR Director, or General Counsel identified an area of risk, s/he would take the matter to the appropriate decision-maker. If the two agreed, then the matter was considered resolved. If not, it was then kicked up to the VP level. If two VPs couldn’t agree, then it landed on my desk.

But I rarely got involved. Most issues were resolved at the first level. Whenever VPs were drawn in, they were predisposed towards long-term cooperation and usually found ways to compromise.

No Easy Answers

Risk management decisions are notoriously complex and unsettling. As Amy Carmichael once observed, “There’s no easy way out of a difficult situation.” Working with all five risk factors—mission, legal, morale, fiscal, and reputational—gives a broader perspective. Wisdom is found in the interplay of competing values and lots of prayer.

*Some fact have been changed from the actual situation.

####

Alec Hill is President Emeritus of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship USA.

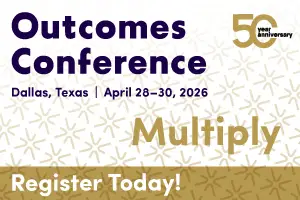

Make plans now to join us for the Outcomes Conference 2025.

We offer nine education tracks and among them is an entire series of workshops on Risk and Legal.

Check out all learnng experiences that have been planned for a leader like you!

2025 Learning Experiences

CLA Membership

Join Christian

Leadership Alliance

A commitment to membership unlocks a more comprehensive access to content, community, and experiential learning. Here are the three membership exclusives that exist to significantly accelerate your professional growth and personal development.